As a German major at Ningbo University, I participated in an exchange program at the University of Szczecin in Poland during the winter semester of 2024-2025. My choice of Poland was driven not only by my interest in the interplay of Central and Eastern European languages and cultures (German and Polish both belong to the Indo-European language family but are from different branches), but also by a desire to apply the cross-cultural theories learned in class in practice. This four-month journey allowed me to achieve multidimensional breakthroughs in academic understanding, language skills, and cultural inclusivity, especially through systematic learning of Polish and obtaining a course completion certificate, which added milestone significance to this experience.

In addition to core courses such as European Cultural Studies and Intercultural Communication, I enrolled in an introductory Polish course designed for international students. The course adopted an "immersive" teaching approach, with two classes per week covering basic grammar, daily conversation (such as shopping and asking for directions), and key vocabulary related to Polish history (like “Solidarność” - the Solidarity movement). Unlike the "precision" of German language teaching in China, the Polish language instructor emphasized "speaking first and correcting later." The class often used role-playing to simulate scenarios like bargaining at a market or making appointments at a hospital, which quickly enhanced practical skills. In Poland, German is the second most commonly used foreign language after English. However, when I proactively used German to inquire in supermarkets and train stations, I found that locals were unable to communicate simply in German, which made me realize the real value of regional language networks.

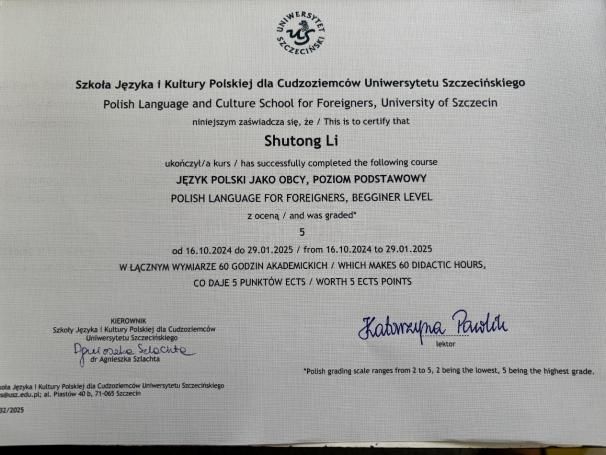

From having no knowledge to passing the A1 exam, I mastered over 700 basic vocabulary words and core grammatical structures (such as the seven cases of nouns). The final project required us to record a video introducing Ningbo in Polish. I highlighted Ningbo's characteristics of "storing ancient and modern knowledge, connecting the world through its ports," resonating with the Polish appreciation for maritime culture, and received the teacher's commendation for "most creative expression."

I was particularly impressed by the "Slavic Digital Archive" at the University of Szczecin library, where I found bilingual German-Polish literature from the 19th century.

At the International Students' Day cultural booth, I designed a "Chinese-Polish Bilingual Challenge" game: participants had to read out the pinyin of Chinese proverbs in Polish (like "Nihao, Polska!") or retell Polish proverbs in Chinese (such as "Gdzie kucharek sześć, tam nie ma co jeść" - "Too many cooks spoil the broth"). During the event, I actively guided visitors in Polish, which validated my speaking skills as reflected in my course completion certificate. In a group discussion, a Polish student mentioned "Germany's compensation to Poland after World War II," and I referenced the historical term "Odra-Neisse Line" learned in class to contribute to the discussion, proposing that "the history of language contact can serve as a carrier of historical memory," which was praised by the professor. This made me realize that language is not just a tool for communication but also a key to unlocking culturally sensitive topics.

At the supermarket checkout, I once confused the Polish words "sześćdziesiąt" (60) and "siedemdziesiąt" (70), resulting in a payment error. After that, I created a "number reference chart" to carry with me.

The differences and similarities in root words (like Polish “książka” for book vs. German “Buch”) and syntax between Polish and German have sparked my strong interest in the evolution of the Indo-European language family. I plan to conduct research on the semantic changes of vocabulary related to the German-Polish war in my graduation thesis. I highly recommend taking language courses in the host country, as even a less commonly spoken language like Polish can greatly enhance the depth of cultural experience.

When I initially applied to exchange at the University of Szczecin, I didn't have many preset expectations. As a German major, my choice of Poland was primarily driven by my interest in the intertwining of Central and Eastern European languages and cultures. Szczecin, located in northwestern Poland near the German border and historically part of Germany, offered a unique geographical and historical background that made it an intriguing environment for language learning.

When I first arrived in Szczecin, the most immediate challenge was the language barrier. Although many young people in Poland generally speak English, many everyday situations still require knowledge of Polish. For instance, when shopping at the supermarket, product labels and conversations with cashiers were primarily in Polish. I enrolled in an introductory Polish course at the University of Szczecin, attending classes four times a week, starting with the basics of pronunciation and grammar. Polish grammar is significantly more complex than German, especially with the seven cases for nouns, which was quite daunting at first. However, my teacher Anna was very good at explaining difficult points using German and English, which helped me gradually find my learning rhythm. By the end of the course, I passed the A1 exam and received a completion certificate. Although my level was still basic, I could at least handle simple conversations in daily life.

The practicality of German here exceeded my expectations. Szczecin is close to Germany, and many older Polish people speak German. Once, when I was buying a ticket at the train station, the ticket clerk directly asked me my destination in German, which surprised and delighted me. I also participated in the school's German corner activities, where I interacted with students from Germany and Austria. Through these activities, I not only improved my speaking skills but also gained a more intuitive understanding of the cultural diversity in German-speaking regions.

In addition to language learning, I took the opportunity to travel to other cities in Poland during my spare time. The Old Town of Kraków and the Auschwitz concentration camp left a deep impression on me. As a German major, visiting the concentration camp was an important historical education. Many of the materials in the exhibition were written in German, allowing me to understand that period of history more directly. In Warsaw, I visited the reconstructed Old Town and discussed the stories of Poland's post-war reconstruction with local students. These travels deepened my understanding of Poland's history and culture.

During the Christmas holiday, I also traveled with a few classmates to Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic. In Berlin, I visited the Brandenburg Gate and the Berlin Wall Memorial, participating in a German-guided tour. The Golden Hall in Vienna and the Charles Bridge in Prague allowed me to experience the richness of Central European culture. These trips not only broadened my horizons but also provided me with practical opportunities to test my language skills.

If I were to mention a regret, it would be that I didn't get to visit the seaside in Gdańsk before leaving. I remember seeing a bilingual German-Polish sign at the harbor once, with the sunset casting long shadows of both languages. Perhaps language is like the tides of the Baltic Sea, washing over the rocky history and ultimately leaving behind scattered shells on the beach.

I would like to express my special gratitude to Katarzyna, a teacher at the language center of the University of Szczecin. When I struggled with the declension rules of Polish, she created memory aids in German to help me break through, perfectly embodying the essence of "cross-cultural teaching."

Li Shutong, BA(German) Candidate, Class of 2022